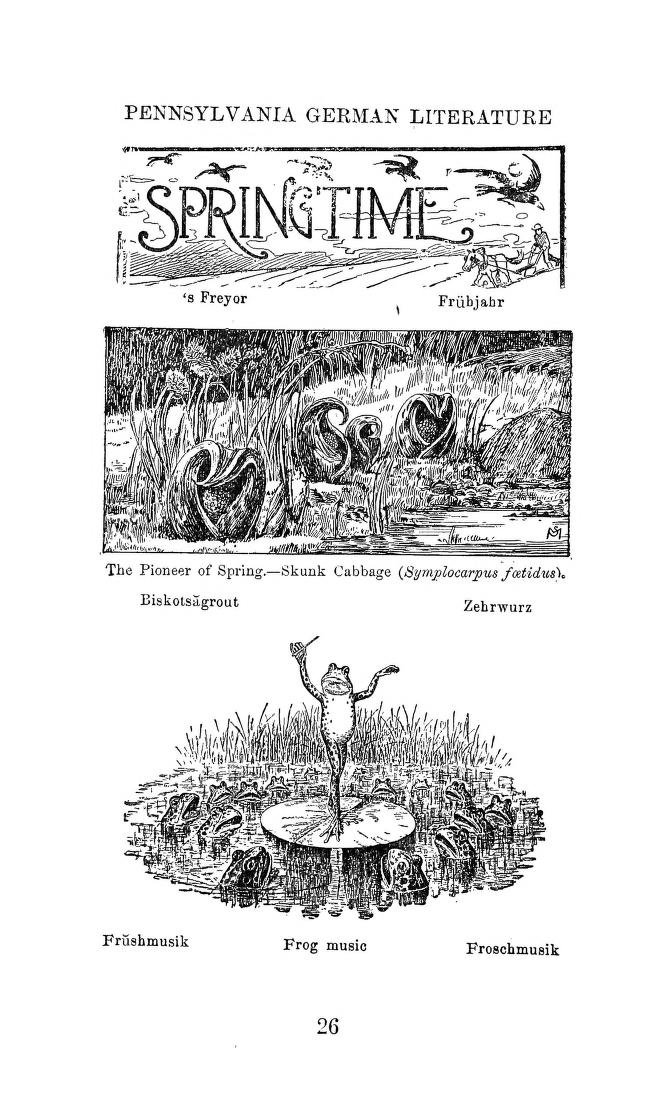

Die Fruschmusik

es Frieyaahr, from Horne’s Pennsylvania German Manual

Homily, Easter 2024, Church of the Holy Spirit, Vashon WA, The Rev. Evan G Clendenin

Listen, do you hear the frogs’ music? Do you hear the song of the rising again?

In recent months, I’ve put some renewed effort into reading and trying to speak some german again. My growing enthusiasm has occassionally spilled over in conversation with some of you-especially about the ongoing class I’m taking in the unique american language, pennsylvania dutch.

Ich winsh eich en froher un hallicher Oschder.

I wish you a happy and holy Easter.

It’s not a language with a mass of state documents, legal texts and magisterial works of art and literature behind it. Despite it’s use being discouraged or forgotten in some places, it is a living language. You might hear varieties at a farmer’s market or horse auction, other local inflections in nursing homes, or gatherings to tell stories, sing songs, and eat a meal that reconnect you to part of who you are. It’s a language less of courthouse and cathedral, and more of workshop, farmstead, kitchen table, walking and working outdoors. It’s no surprise that one should find the following word in a 19th century Deitsch wordlist: Fruschmusik. Frog music. A word that helps you tell of what you have heard, say, while working in the pasture near that little wetland in the woodlot, near that time when the frogs begin to sing.

You may have heard this music yourself recently. Well, a couple weeks ago, I was out for a run near my home. I took a new route, and found a little trail that dipped down through one of the little kettles, the little depressed wetlands left over from a recent glacial period that dot the south puget sound, and left a lot of gravel up this way. As I neared the kettle pond, I could hear the sound of the frogs. It grew louder and louder. I stopped running, slowed to a walk, then stopped. And I found myself surrounded by truly overwhelming music, and in the music a tremendous force. I mean, I thought for a second the sheer vibration of those countless frogs singing just might stop my heart.

If you were to stand there amidst the music of frogs cracking the mud with the new life of song, you might think of prophets who see angels approach, and tremble, or God who warns Moses that no one can see me and live. Or you might wonder what it was like to stand a little distance from the cross as Jesus died, and the curtain tore, and the sun stopped. Or to approach the tomb that easter morning, exhausted with grief and fear, and stand there, a nameless stranger, maybe the landscaper, speaks. Was it like the rushing of a shell held to you ear? The roar of a blast furnace or a copper smelter? Or the unearthly music of countless tiny frogs lovely and fearsome enough to stop your heart?

“O for a thousand tongues to sing my dear redeemers praise!” wrote Charles Wesley!

And when Mary and others went away from that music, well, what did they say of it? In tongues, what speech? The gospels were written down later, and even then, not the greek of homer or sappho or aristotle, but in the common speech that grew up from many dialects first thrown together into military service and trade. Before that, written in letters, letters of love and guidance written from the road, on ships, in prison, during a quiet and clear moment during a break from work, or resting at day’s end.

And before that it was stories, and songs, and prayers, passed along in the language of workshop and street, field and seaport, nursery, upper rooms, kitchens, riversides, and even a few corners of worldly power. And what did they tell, but of the unearthly music, the music that could stop your heart and start it again with awe, with joy, hearing that Christ has cracked open the ground and risen in a song heard with hope through all creation.

Ich beed as eich ebbes vun der Fruschmusik heert, un ebbes davun saagt.

I pray that you hear something of the Frogs’ music, and say something of it.